|

Politics

in the 12th and 13th centuries:

|

Popes

|

Emperors

|

|

Alexander

III, 1159–81

|

Frederick

I, Barbarossa, 1152–90

|

|

Innocent

III, 1198–1216

|

Henry

VI, 1190–97

|

|

Gregory

IX, 1227–41

|

Frederick

II, 1215–50

|

|

Innocent

IV, 1243–1254

|

Rudolf

of Hapsburg, 1273–91

|

|

Boniface

VIII, 1294–1303

|

Adolf

of Nassau,

1292–98

|

|

England

|

France

|

|

Henry

I, 1100–1135

|

|

|

Henry

II, 1154–1189

|

Louis

VII, 1137–80

|

|

John,

1199–1216

|

Philip

II, Augustus, 1180–1223

|

|

Henry

III, 1216–1272

|

Louis

IX, saint, 1226–70

|

|

Edward

I, 1272–1307

|

Philip

IV, the Fair, 1285–1314

|

|

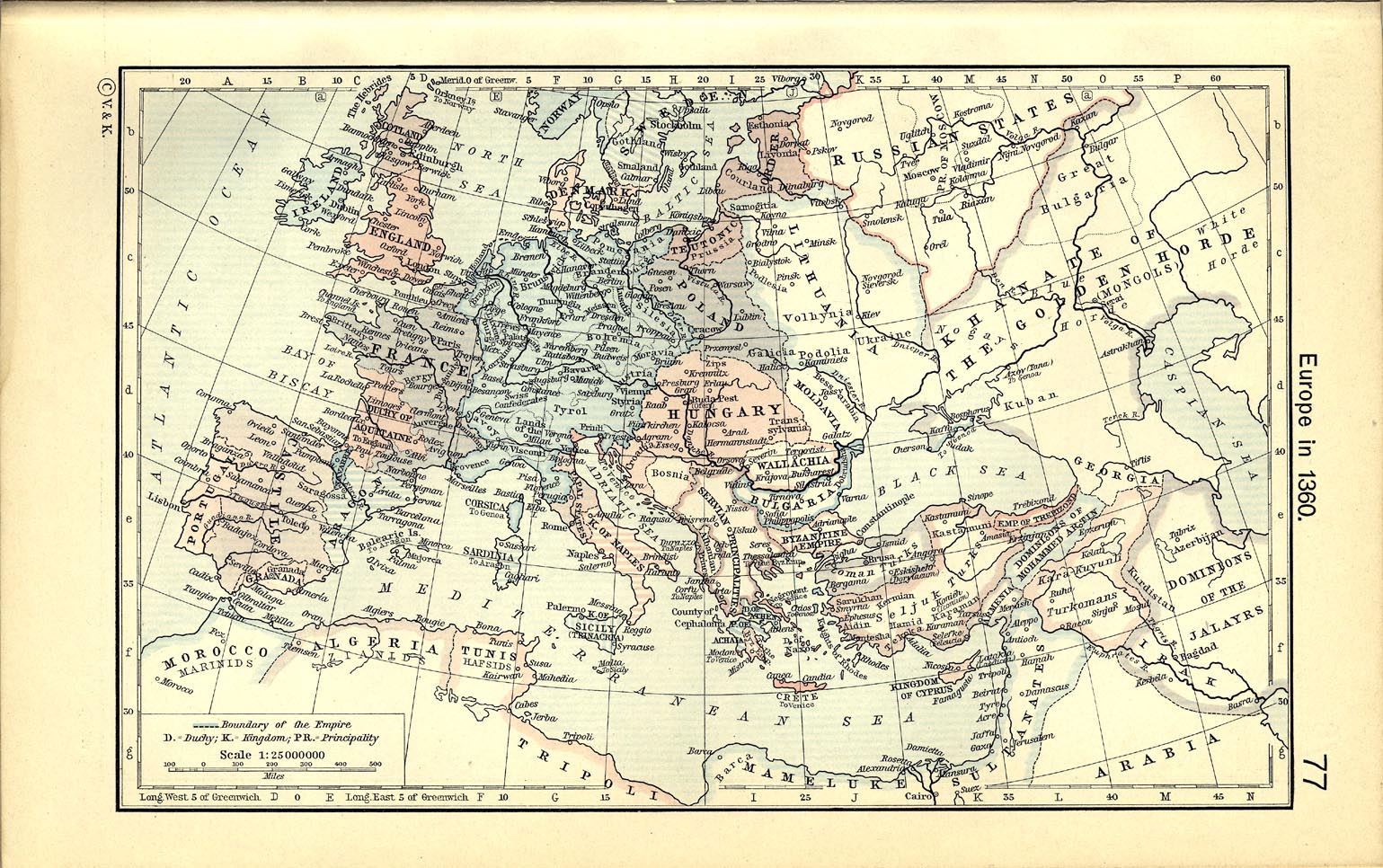

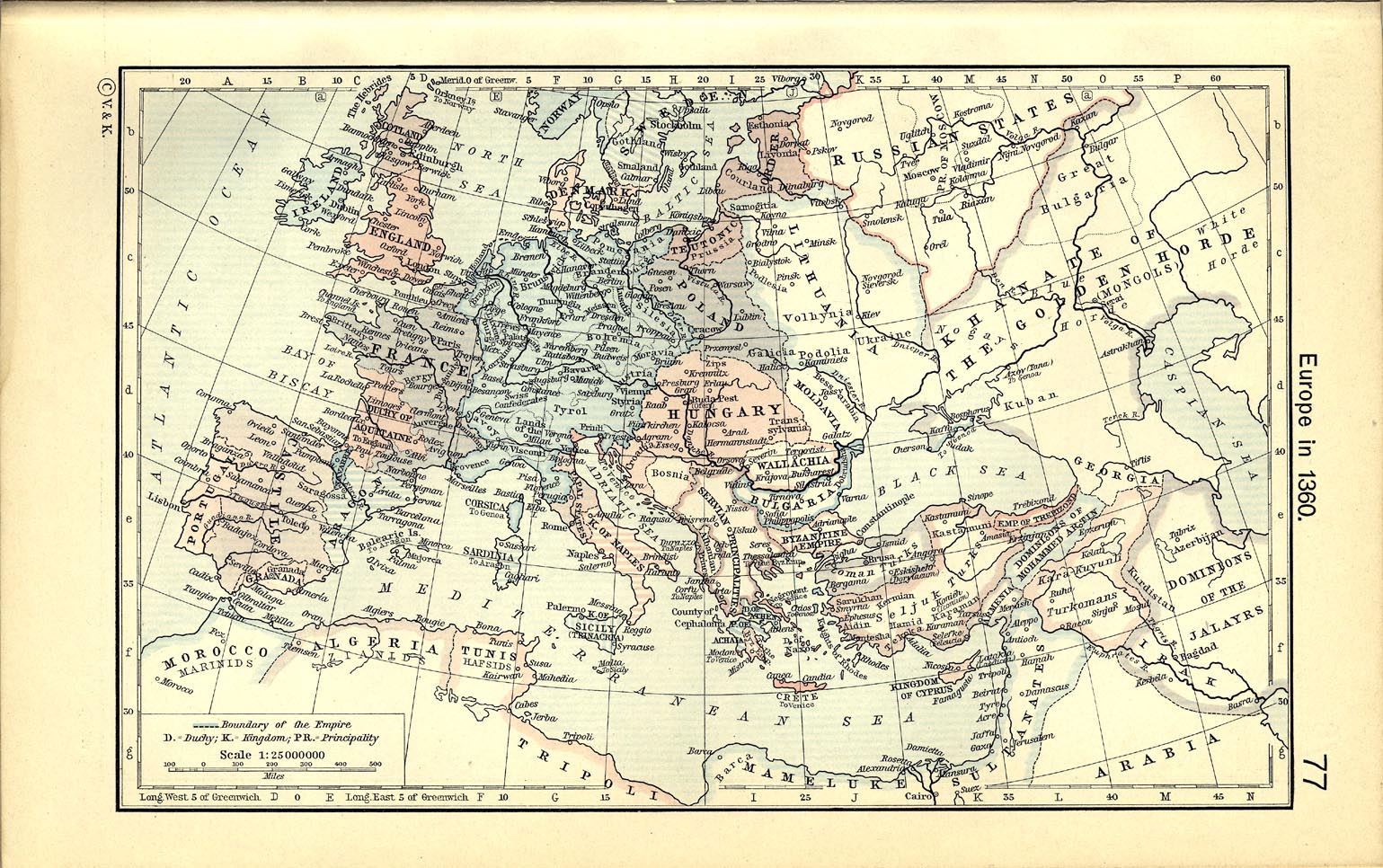

Iberian

Peninsula

|

Sicily (in the broad sense)

|

|

Alfons

VI, Castile,

1065–1109

|

Roger

II, 1130–1154

|

|

Raymond

Berenger IV, Catalonia,

1131–62

|

|

|

Peter

II, Aragon, 1196–1213

|

Henry

VI, see above

|

|

Ferdinand

III, Castile,

1217–1252

|

Frederick

II, 1197–1250

|

|

James

I, Aragon, 1213–1276

|

Charles

of Anjou,

1265–1285

|

|

Alfons

X, the Wise, Castile,

1252–84

|

Peter

of Aragon,

1282–85

|

Empire and papacy

1.

The Diet of Worms (settlement of the

invesiture controversy)—1122

2.

The commune movement

a.

Frederick Barbarossa crushes Roman

commune—1155

b.

Lombard League supports Alexander III, defeats

Barbarossa—1176

3.

Sicily and Naples

a.

Constance of Sicily, daughter of the Norman

king Roger II, marries Henry VI of Germany, their son was Frederick

II

b.

Frederick II deposed by Innocent IV at the

council of Lyons

in 1245

c.

Charles of Anjou, the younger brother of Louis

IX of France, conquers Sicily—1266

4.

Richard of Cornwall of England and Alfons the

Wise of Castille vie for the impreial crown, but the electors give it to

Rudolf of Hapsburg

5.

The electors depose Adlof of Nasau—1298

6.

The effect of the collapse of the Hohenstaufen

dynasty

England

1.

Relatively unified as a result of the Conquest

in 1066.

2.

Henry I develops the most powerful centralized

fiscal and judicial institutions in all of Europe.

3.

The Norman kings were also dukes of Normandy. Henry II’s

marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine made him lord of an empire that included not

only England but the

western half of France

as well. Control of such an empire demanded strong delegates in England

to mind the store while Henry was away.

4.

John lost Nomandy in 1204 and with it much of

the Angevin empire. The struggles that ensued with his own baronage and which

led to Magna Carta in 1215 and the strugges of his son Henry III with the

same baronage did not have to result in the development of parliament at the

end of the 13th century but that institution is easiser to understand if we

keep those struggles in mind.

France

1.

Where England

began the 12th century strong, France began it weak. The French

king was surrounded by powerful vassals, including the king of England, the count of Flanders, the duke of Burgundy, the count of Blois

and Champagne, and the count of Toulouse.

2.

The French king had effective power only in

the royal domain, at the beginning of the 12th century only a relatively

small region around Paris and Orléans.

3.

Philip Augustus recovered for the French crown

all of the northern domains of the English king, Normandy,

Brittany, Maine, Anjou

and Poitou, and developed central financial

institutions within the royal domain. He parallels the role of Henry I of England,

a half a century later.

4.

The Albigensian crusade in the beginning of

the thirteenth century ended by uniting the great province

of Languedoc to the French crown,

and eliminating the independence of the count of Toulouse

and virtually eliminating the power of Aragon

on the northern side of the Pyrenees.

5.

Louis IX and Philip the Fair were able to

consolidate these achievements, to develop institutions both judicial and

financial that would ensure both royal order and royal control within this

greatly expanded royal domain. By the end of Philip’s reign, we have clear

indications of an institution known as the parlement of Paris and the beginning of an institution

called the estates general. These institutions divided between them what was

done in England

in one parliament.

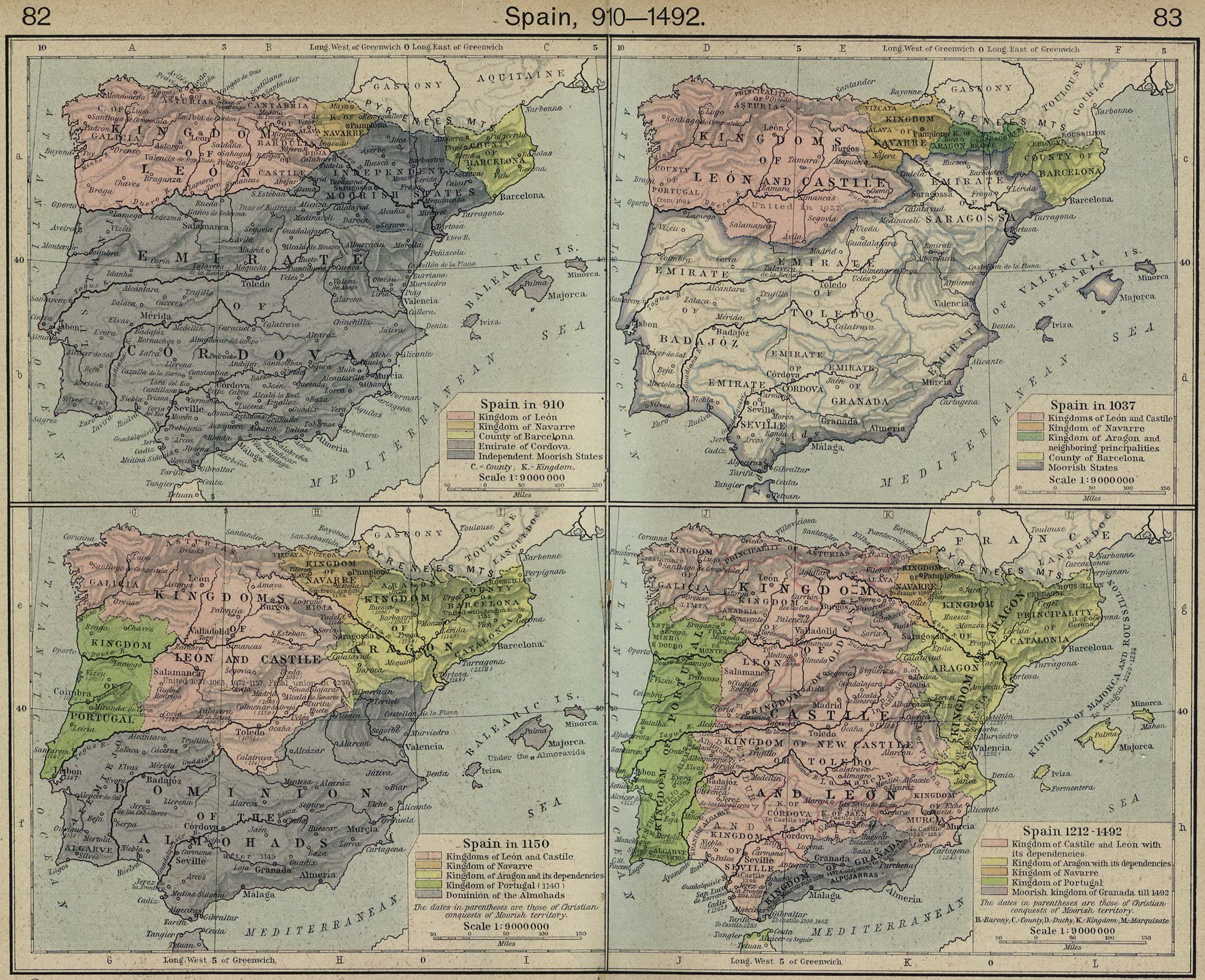

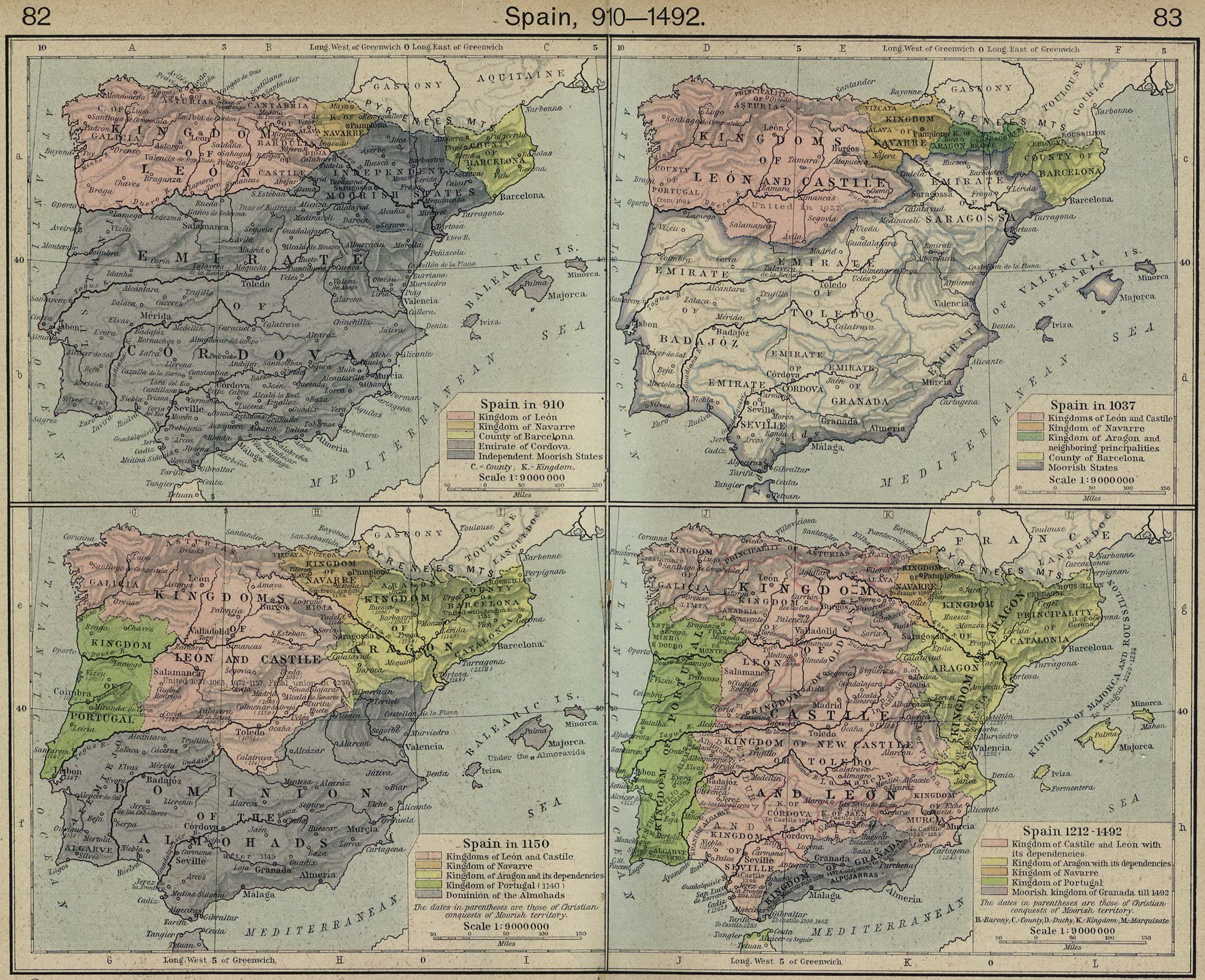

Castile and Aragon

1.

In the 11th century the Christians in the

northern fringe of the peninsula were organized into small kingdoms: Leon, Castille, Navarre,

Aragon, and the county

of Barcelona.

2.

By the beginning of the 12th century Alfons VI

of Castile succeeded in

uniting the crowns of Leon

and Castile and recovering

the center of Spain, as

far south as Toledo.

3.

In the mid–12th century, Portugal became a separate

kingdom.

4.

In 1137, Raymond Berenguer IV, count of Barcelona, united Catalonia

with Aragon

by marrying the heiress to the Aragonese crown. Peter II of Aragon sided with the Albigensians and lost

most of the control that Aragon

had in southern France.

His son, however, James I, conquered the Baleric

Islands; later he reconquered Valencia

from the Moors. He established his son Peter on the throne of Sicily (the island only) and Sicily

became divided from the kingdom

of Naples, a situation

that was to last into the 15th century.

5.

In the meantime, James’s contemporary

Ferdinand III of Castile

recovered most the center of what is now Spain

for Castile.

By 1250 all remained in Moorish hands was a small area around Granada. It was to

remain in Moorish hands until 1492, 18 yrs after the the crowns of Castile and Aragon were united under

Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile.

Alfons X of Castile

had the job of consolidation and establishing institutions. He was only partially successful. Alfons never succeded completely in

bringing the nobility under his control. Leon,

though it was united with Castile,

had its separate cortes, an institution that roughly

corresponds to the English parliament.

Similarly, though the kingdom

of Aragon, the county

of Barcelona (now increasingly

called Catalonia) and the principality of Valencia

were all united under one crown, each had its own cortes. The nobility was strong in Aragon and Valencia,

the cities in Catalonia. Navarre

was not united with the rest of Spain until the 16th century.

|