OUTLINE — LECTURE 3

(For a more “printer-friendly” version of this outline (pdf) click here.)

NON-ROMAN LAW IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE

ÆTHELBERT’S ‘CODE’1. The circumstancesFrom Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation (completed around 732) [From Dorothy Whitelock trans. in English Historical Documents, 2d ed., vol. 1, pp. 663–64]: ‘In the

year of our Lord's incarnation 616, which is the 21st year after Augustine

with his companions was sent [by Pope Gregory the Great] to preach to the

nation of the English, Ethelbert, king of the people of Kent, after his

temporal kingdom which he held most gloriously for 56 years, entered into the

eternal joys of the heavenly kingdom. He was indeed the third of the kings in

the nation of the English to hold dominion over all their southern provinces,

which are divided from the northern by the river

‘Among

the other benefits which in his care for his people he conferred on them, he

also established for them with the advice of his councillors [cum consilio sapientium] judicial

decrees [decreta iudicialia] after

the example of the Romans [iuxta

exempla Romanorum], which, written in the English language, are preserved

to this day and observed by them; in which he first laid down how he who

would steal any of the property of the Church, of the bishop, or of other

orders, ought to make amends for it, desiring to give protection to those

whom, along with their teaching, he had received.’

2. The Manuscript

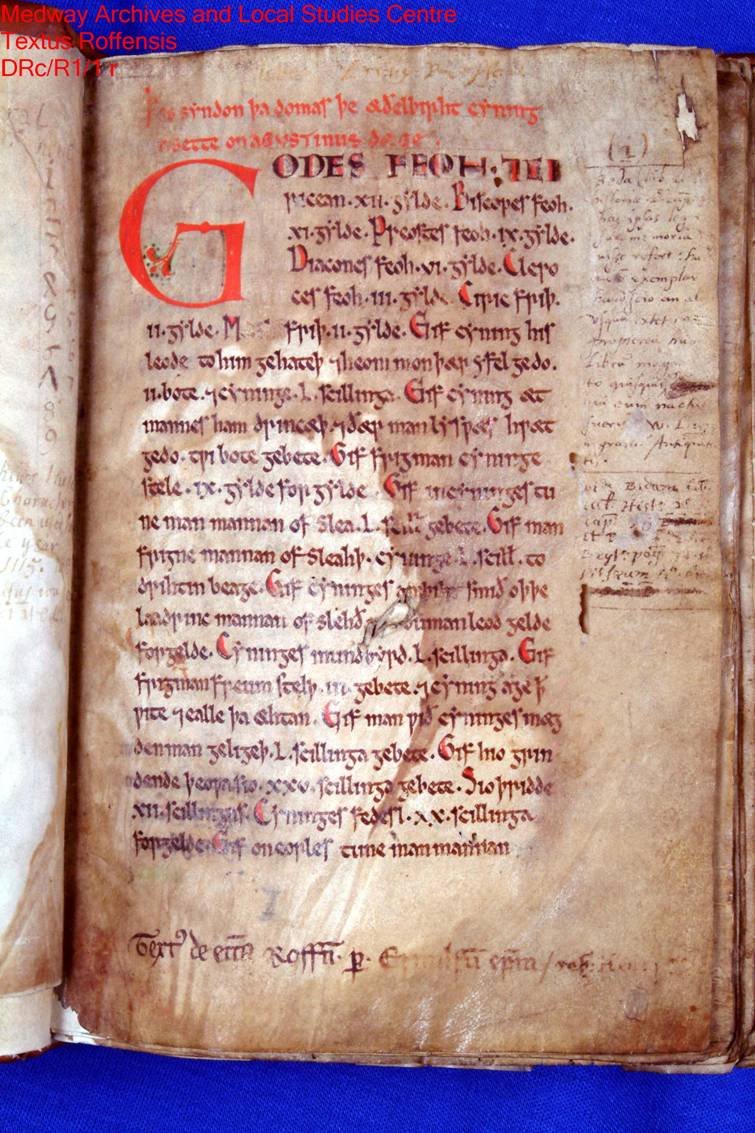

The laws of Æthelberht of Kent, the first page of the only manuscript copy, the Textus Roffensis, from the collection of the Dean and Chapter of Rochester Cathedral, now housed in the Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre in Strood (near Rochester), Kent. The photograph is is a download from the archive’s website.

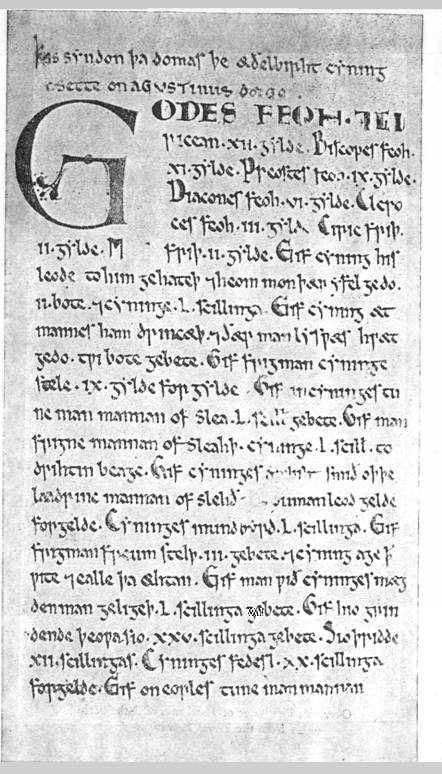

From the frontispiece of H. G. Richardson and G. O.

Sayles, Law and Legislation from

Æthelberht to Magna Carta (

3. Notes on the Words in Bede

4. Æthelbert’s Code cc. 1-7, 10 with a Literal Translation1. Godes feoh 7 ciricean XII gylde. God’s property and church’s 12 by payment. 2. Biscopes feoh XI gylde. Bishop’s property 11 by payment. 3. Preostes feoh IX gylde. Priest’s property 9 by payment. 4. Diacones feoh VI gylde. Deacon’s property 6 by payment. 5. Cleroces feoh III gylde. Cleric’s property 3 by payment. 6. Ciricfri~ II gylde. Church peace 2 by payment. 7. M[fthl]fri~ II gylde. Assembly peace 2 by payment. 10. Gif frigman cyninge stele, IX gylde forgylde. If a freeman steals from the king, let him pay forth 9 by payment. 5. Method

6. Outline of Æthelbert's Codea. The Church cc. 1–7 b. The king cc. 8–17 c. Eorls cc. 18–19 d. Ceorls cc. 20–71 cc. 20–31 mundbyrd, wergeld, property offenses cc. 32–71 personal injury, arranged from head to toe e. Women cc. 72–77 f. Servants, slaves cc. 78–83 7. Basic Conceptsa. wergeld. Wer is cognate with Latin vir, a male person; geld is our word ‘gold’ but it’s broader: literally ‘man-payment’ or ‘man-price’. b. mundbyrd. The mund part means ‘protection’; it is cognate with Latin manus, ‘hand’. The byrd part is harder, but it is probably related to our word ‘border’, hence mundbyrd is ‘area of protection’. c. friþ pronounced frith, cognate with Modern German Friede, ‘peace’. d. bot (‘compensation’) occurs very frequently particularly in the verbal form gebete (‘let him make compensation’); wite (‘fine’, ‘penalty’) only once in c.15, but there’s a number of offenses to the king’s mundbyrd e. This is clearly not criminal law, but it’s not quite civil either. f. One may doubt if these are absolute liability offenses. 8. The sorts and conditions of men: A comparison of Æthelbert’s code and Ine’s (West Saxon, roughly 695)A TABLE OF WERGELDS

a In Hlothere & Eadric 1.

b @ 20 pence to the shilling.

c @ 5 pence to the shilling.

Price lists from London in the first half of the 10th century value an ox at 30 pennies, a cow at 20, a pig at 10, a sheep at 5. Probably no ordinary ceorl in Athelbert’s Kent could command 400 sheep, and precious few kingroups of ceorlas could. 9. An Insular ComparisonFrom an Irish Penitential of c.800 (McNeil and Gamer p. 165):

Ch.5 Of anger. 2. Anyone who kills his son or daughter does penance twenty-one years. Anyone who kills his mother or father does penance fourteen years. Anyone who kills his brother or sister or the sister of his mother or father, or the brother of his father or mother, does penance ten years: and this rule is to be followed to seven degrees both of the mother's and father's kinto the grandson and great-grandson and great-great-grandson, and the sons of the great-great-grandson, as far as the finger-nails. ... Seven years of penance are assigned for all other homicides; excepting persons in orders, such as a bishop or a priest, for the power to fix penance rests with the king who is over the laity, and with the bishop, whether it be exile for life, or penance for life. If the offender can pay fines, his penance is less in proportion. Ch. 4 Of envy. 5. ... There are four cases in

which it is right to find fault with the evil that is in a man who will not

accept cure by means of entreaty and kindness: either to prevent someone else

from abetting him to this evil; or to correct the evil itself; or to confirm

the good; or out of compassion for him who does the evil. But anyone who does

not do it for one of these four reasons, is a fault-finder, and does penance

four days, or recites the hundred and fifty psalms naked.

10. The bottom line

|

|

|

|

| [Home Page] [Syllabus Undergraduate] [Syllabus Law and Graduate] [Lectures Undergraduate] [Lectures Law and Graduate] [Information and Announcements] URL: http://www.law.harvard.edu/faculty/cdonahue/courses/CLH/lectures/outl03.html Copyright © 2011 Charles Donahue, Jr.

|